By Ray Bennett

By Ray Bennett

LONDON – The myth surrounding Marlon Brando, who was born 100 years ago today, has centred not only on his brilliant acting in films such as ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ (with Vivien Leigh above), ‘On the Waterfront’, ‘The Godfather’ and ‘Apocalypse Now’ but also his eccentric ways and latterly immense girth.

It’s instructive to recall what he was like as a young man when he burst into worldwide fame on stage and screen. When he made his first movie – ‘The Men’ (below left) in 1950, a story about disabled war veterans – Brando spent six weeks living in a hospital ward of paraplegic soldiers. Determined to recreate their reality on film, he shared their lives and won their confidence.

In the evenings, he joined them at a Los Angeles bar sitting in a wheelchair just as they did. One night, according to biographer Charles Higham, a woman entered the place whom Brando recognised as a notorious fake evangelist.

In the evenings, he joined them at a Los Angeles bar sitting in a wheelchair just as they did. One night, according to biographer Charles Higham, a woman entered the place whom Brando recognised as a notorious fake evangelist.

‘You poor man,’ she told the actor. ‘Wouldn’t you like to walk again? I have the power.’

Brando decided to play along, Higham writes: ‘Marlon let out a long sigh and stood up pretenting to be a little shakey. Then, slowly but surely he began to dance around the room terminating with a frenzied jig that had all of the veterans hysterical with laughter.’

The depth of the actor’s feelings for those undefeated soldiers is in every frame of ‘The Men’ and that night says a lot about Marlon Brando – the man, not the myth. He was always a curious mix of animal magnetism, intellectual irony and childlike mirth. Born in Omaha, his acting instincts and impish nature were soon revealed. He excelled at swimming and American football and when he moved to New York in 1943 to study acting his physique was a plus. His electrifying success in the Tennessee Williams play ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ on Broadway in December 1947 owed as much to his sex appeal as it did to his obvious acting prowess.

When he made the screen version of ‘Streetcar’ in 1951, his oddball sense of humour was unleashed. Biographer Higham writes that Brando reputedly put urine in a cast member’s beer and when he saw co-star Kim Hunter jump at the sight of a spider, he conspired to lower a fake one through her dressing room window eliciting considerable screaming.

When he made the screen version of ‘Streetcar’ in 1951, his oddball sense of humour was unleashed. Biographer Higham writes that Brando reputedly put urine in a cast member’s beer and when he saw co-star Kim Hunter jump at the sight of a spider, he conspired to lower a fake one through her dressing room window eliciting considerable screaming.

At first, Brando did not relate to his British leading lady, Vivien Leigh, as he found her delivery to be affected and false. According to Higham, her very English manners bothered him so much that he demanded, ‘Why are you so fucking polite?’

That all changed when the actor learned that Leigh was suffering from tubeculosis. Leigh biographer Anne Edwards writes, ‘Brando would sing folk songs for her in a pleasant voice and do imitations of Laurence Olivier (Leigh’s then husband) as Henry V.’

Leigh won an Oscar for her performance as did Hunter and Karl Malden. Brando was nominated but lost to Humphrey Bogart in ‘The African Queen’. In 1954, it was a different story with ‘On the Waterfront’ (with Rod Steiger above). A gritty drama about corruption in the longshoremen’s union in New York’s dockland, it survives today as a forceful depiction of betrayal enhanced by brilliant acting. At the time, for the liberal Brando it was a reminder of betrayal of anoter kind.

Coming soon after anti-communist witch-hunts by Senator Joseph McCarthy, the movie involved several people who had informed on their friends including director Elia Kazan, writer Budd Schulberg and co-star Lee J. Cobb.

Coming soon after anti-communist witch-hunts by Senator Joseph McCarthy, the movie involved several people who had informed on their friends including director Elia Kazan, writer Budd Schulberg and co-star Lee J. Cobb.

Brando hated ‘On the Waterfront’ according to Higham and for years went into a rage whenever Kazan’s name was mentioned although supposedly he later forgave him. They both won Academy Awards and Brando accepted his Oscar from Bette Davis. ‘I can’t remember what I was going to say for the life of me,’ the actor said. ‘I didn’t think ever in my life that so many people were so directly responsible for me being so very, very happy.’

Such was Brando’s pre-eminence that even today his next film, ‘Guys and Dolls’ – Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s film version of the Frank Loesser musical ‘Guys and Dolls’ based on writer Damon Runyon’s stylised New York gangster stories – is noted more for his appearance than the Frank Sinatra vehicle it might otherwise have been.

Sinatra was not happy anyway. He had wanted the Brando role in ‘On the Waterfront’ and now Brando was playing the show’s romantic leading man Sky Masterson while Sinatra accepted the second-lead, Nathan Detroit. The singer also came to the set fully prepared and liked to ace his performances in one take, Higham writes. Method-actor Brando took his time. On the first day of shooting, a nightclub scene in which Sinatra had to eat cheesecake while Brando talked, things took a turn for the worse. After eight takes, Sinatra exploded: ‘These fucking New York actors! How much cake do you think I can eat?’

Sinatra was not happy anyway. He had wanted the Brando role in ‘On the Waterfront’ and now Brando was playing the show’s romantic leading man Sky Masterson while Sinatra accepted the second-lead, Nathan Detroit. The singer also came to the set fully prepared and liked to ace his performances in one take, Higham writes. Method-actor Brando took his time. On the first day of shooting, a nightclub scene in which Sinatra had to eat cheesecake while Brando talked, things took a turn for the worse. After eight takes, Sinatra exploded: ‘These fucking New York actors! How much cake do you think I can eat?’

It was not the first time Brando had a fight on a movie set. On the 1962 picture ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’, he went through three directors. Carol Reed walked away after Brando objected to the script making Captain Bligh the main focus rather than his rebellious character Fletcher Christian. Trevor Howard (with Brando above left) told me years later that Reed would not suffer Brando’s tantrums. Howard said he got along with his co-star but lamented the change in the direction of the script, which came in fits and starts from Hollywood. Lewis Milestone compleated most of the film but finally quit in exasperation so George Seaton directed the climax of the film.

Brando’s abrupt revisions of how he played Christian turned other cast members against him. Irish actor Richard Harris had several run-ins with the star according to biographers. In one scene, Brando was supposed to slap Harris in the face but he kept pulling back rather than give him a real clout. Annoyed after several useless takes, Harris said, ‘Why don’t you kiss me and be done with it?’

Brando’s abrupt revisions of how he played Christian turned other cast members against him. Irish actor Richard Harris had several run-ins with the star according to biographers. In one scene, Brando was supposed to slap Harris in the face but he kept pulling back rather than give him a real clout. Annoyed after several useless takes, Harris said, ‘Why don’t you kiss me and be done with it?’

The film was a flop but Brando seemed to find peace in the South Pacific. After notoriously failed marriages, he settled on an island there leaving only to make a series of cinematic bombs. It was not until he made ‘The Godfather’ (above) in 1972 that he redeemed himself.

Director Francis Ford Coppola bought Mario Puzo’s bestselling gangster novel and immediately actors from Danny Thomas to Burt Lancaster made it known they were available for the role of family patriarch Don Corleone. Coppola wanted one of two actors – Laurence Olivier or Marlon Brando.

Brando agreed to audition and while the story of his stuffing his cheeks with tissue paper has been disputed, he landed the role. During production, his impish humour surfaced and he got into ‘mooning’ contests with co-stars James Caan and Robert Duvall but it became clear that his work on the film was remarkable.

Brando won his second Oscar but famously refused to accept it. His next movie, ‘Last Tango in Paris’, later the subject of accusations over director Bernardo Berlusconis cruel treatment of co-star Maria Schneider, marked a return to sexual intensity matched by his disturbing portrayal of deranged warrrior Col. Kurtz in Coppola’s Vietnam masterpiece ‘Apocalypse Now.’

Brando won his second Oscar but famously refused to accept it. His next movie, ‘Last Tango in Paris’, later the subject of accusations over director Bernardo Berlusconis cruel treatment of co-star Maria Schneider, marked a return to sexual intensity matched by his disturbing portrayal of deranged warrrior Col. Kurtz in Coppola’s Vietnam masterpiece ‘Apocalypse Now.’

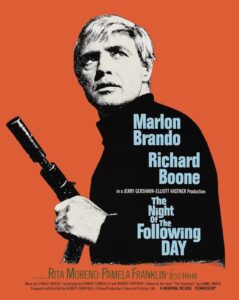

It was largely downhill after that although ‘The Formula’, ‘A Dry White Season’, ‘The Freshman’ and ‘Don Juan DeMarco’ made up for dross such as ‘The Island of Dr. Moreau.’ Some of us remain fond of earlier pictures such as ‘The Young Lions’, ‘One-Eyed Jacks’, ‘The Ugly American’, ‘Reflections in a Golden Eye’, ‘The Night of the Following Day’, and ‘The Missouri Breaks’.

He died aged 80 on July 1 2004

Marlon Brando: the man behind the myth

LONDON – The myth surrounding Marlon Brando, who was born 100 years ago today, has centred not only on his brilliant acting in films such as ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ (with Vivien Leigh above), ‘On the Waterfront’, ‘The Godfather’ and ‘Apocalypse Now’ but also his eccentric ways and latterly immense girth.

It’s instructive to recall what he was like as a young man when he burst into worldwide fame on stage and screen. When he made his first movie – ‘The Men’ (below left) in 1950, a story about disabled war veterans – Brando spent six weeks living in a hospital ward of paraplegic soldiers. Determined to recreate their reality on film, he shared their lives and won their confidence.

‘You poor man,’ she told the actor. ‘Wouldn’t you like to walk again? I have the power.’

Brando decided to play along, Higham writes: ‘Marlon let out a long sigh and stood up pretenting to be a little shakey. Then, slowly but surely he began to dance around the room terminating with a frenzied jig that had all of the veterans hysterical with laughter.’

The depth of the actor’s feelings for those undefeated soldiers is in every frame of ‘The Men’ and that night says a lot about Marlon Brando – the man, not the myth. He was always a curious mix of animal magnetism, intellectual irony and childlike mirth. Born in Omaha, his acting instincts and impish nature were soon revealed. He excelled at swimming and American football and when he moved to New York in 1943 to study acting his physique was a plus. His electrifying success in the Tennessee Williams play ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ on Broadway in December 1947 owed as much to his sex appeal as it did to his obvious acting prowess.

At first, Brando did not relate to his British leading lady, Vivien Leigh, as he found her delivery to be affected and false. According to Higham, her very English manners bothered him so much that he demanded, ‘Why are you so fucking polite?’

That all changed when the actor learned that Leigh was suffering from tubeculosis. Leigh biographer Anne Edwards writes, ‘Brando would sing folk songs for her in a pleasant voice and do imitations of Laurence Olivier (Leigh’s then husband) as Henry V.’

Leigh won an Oscar for her performance as did Hunter and Karl Malden. Brando was nominated but lost to Humphrey Bogart in ‘The African Queen’. In 1954, it was a different story with ‘On the Waterfront’ (with Rod Steiger above). A gritty drama about corruption in the longshoremen’s union in New York’s dockland, it survives today as a forceful depiction of betrayal enhanced by brilliant acting. At the time, for the liberal Brando it was a reminder of betrayal of anoter kind.

Brando hated ‘On the Waterfront’ according to Higham and for years went into a rage whenever Kazan’s name was mentioned although supposedly he later forgave him. They both won Academy Awards and Brando accepted his Oscar from Bette Davis. ‘I can’t remember what I was going to say for the life of me,’ the actor said. ‘I didn’t think ever in my life that so many people were so directly responsible for me being so very, very happy.’

Such was Brando’s pre-eminence that even today his next film, ‘Guys and Dolls’ – Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s film version of the Frank Loesser musical ‘Guys and Dolls’ based on writer Damon Runyon’s stylised New York gangster stories – is noted more for his appearance than the Frank Sinatra vehicle it might otherwise have been.

It was not the first time Brando had a fight on a movie set. On the 1962 picture ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’, he went through three directors. Carol Reed walked away after Brando objected to the script making Captain Bligh the main focus rather than his rebellious character Fletcher Christian. Trevor Howard (with Brando above left) told me years later that Reed would not suffer Brando’s tantrums. Howard said he got along with his co-star but lamented the change in the direction of the script, which came in fits and starts from Hollywood. Lewis Milestone compleated most of the film but finally quit in exasperation so George Seaton directed the climax of the film.

The film was a flop but Brando seemed to find peace in the South Pacific. After notoriously failed marriages, he settled on an island there leaving only to make a series of cinematic bombs. It was not until he made ‘The Godfather’ (above) in 1972 that he redeemed himself.

Director Francis Ford Coppola bought Mario Puzo’s bestselling gangster novel and immediately actors from Danny Thomas to Burt Lancaster made it known they were available for the role of family patriarch Don Corleone. Coppola wanted one of two actors – Laurence Olivier or Marlon Brando.

Brando agreed to audition and while the story of his stuffing his cheeks with tissue paper has been disputed, he landed the role. During production, his impish humour surfaced and he got into ‘mooning’ contests with co-stars James Caan and Robert Duvall but it became clear that his work on the film was remarkable.

It was largely downhill after that although ‘The Formula’, ‘A Dry White Season’, ‘The Freshman’ and ‘Don Juan DeMarco’ made up for dross such as ‘The Island of Dr. Moreau.’ Some of us remain fond of earlier pictures such as ‘The Young Lions’, ‘One-Eyed Jacks’, ‘The Ugly American’, ‘Reflections in a Golden Eye’, ‘The Night of the Following Day’, and ‘The Missouri Breaks’.

He died aged 80 on July 1 2004